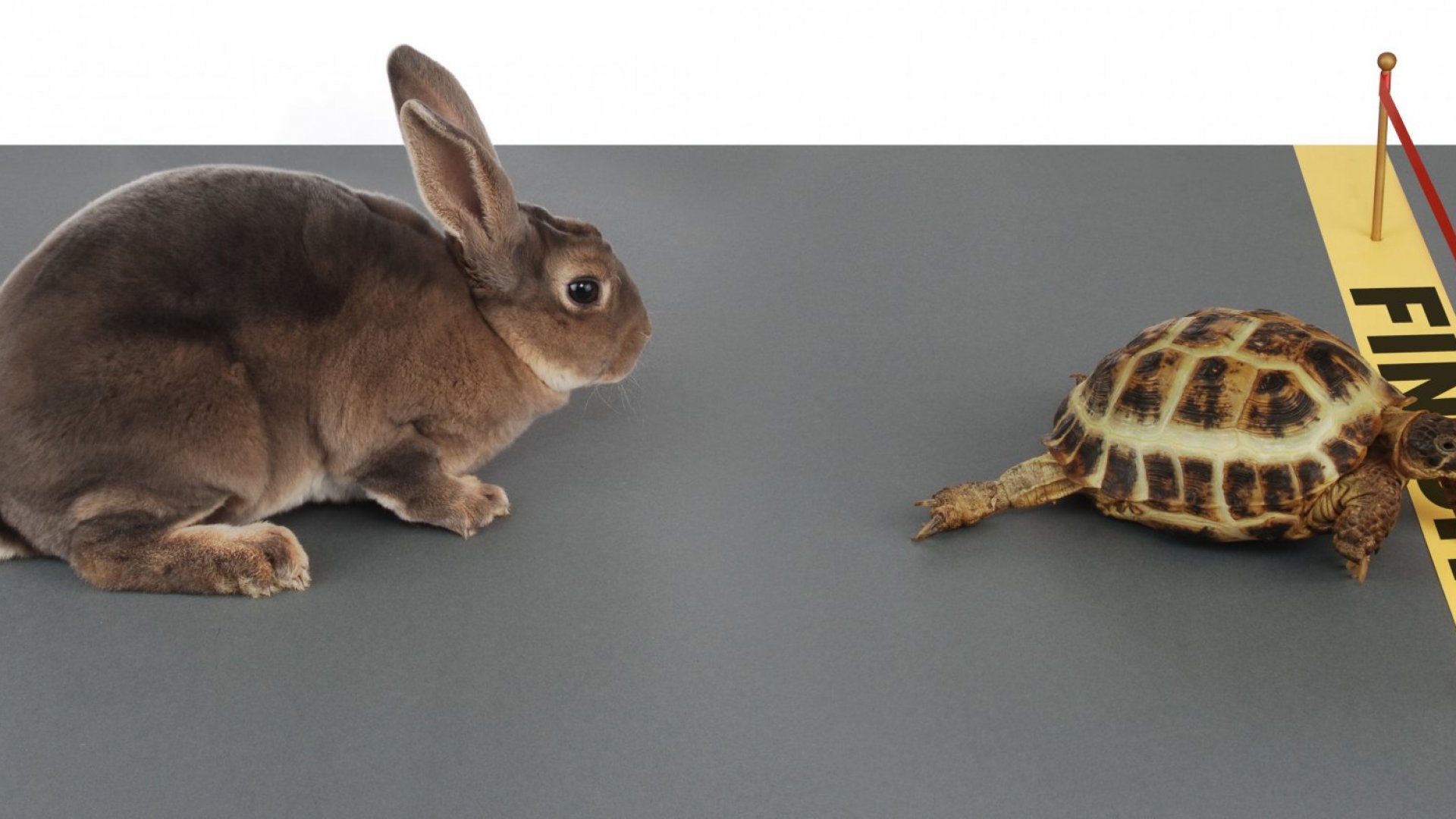

Sometimes, it’s important to slow down in order to speed up.

I was reminded of this paradox while listening to John C. Maxwell’s podcast on “How to Leadershift Successfully”.

This episode centres on how to effect change from without through starting the transformation journey from within, as part of the process of becoming a better leader.

In the recording, Maxwell touches on the concept of “fast forward”, where societal and global change has been taking place in faster and shorter cycles.

While talking about it, he says:

I love people who say, You know what, I tell you what: It’s just the pace is going crazy; I can hardly wait for things to slow down. (Pause.) Slow down. (Pause.) That means you’re gonna die. (Laughter from the audience.) Things aren’t gonna slow down. Fast is faster. And it keeps going – with technology and social media, fast just gets faster. I mean, fast isn’t gonna get slower; fast isn’t gonna stop; fast isn’t gonna call “time-out”. Fast is faster.

The insinuation: when someone talks about “slowing down”, they are both resistant to change and unaware that change is the only constant in life.

On the surface, Maxwell’s reading makes sense. Diffusion of innovations theory posits that there will always be laggards in some way, shape or form.

But there’s the rub. Both theory and practical experience show that it’s not that people don’t change or don’t want to change.

If they will change – eventually – then where is this resistance, that Maxwell is describing, coming from?

In addressing the matter of resistance, Maxwell himself is instructive, having previously mentioned:

Don’t pretend resistance will go away on its own. Draw it into the open. Invite the voices of discontent to the table. Put your pride aside and listen. Remember, it isn’t personal. You can’t deal with resistance until you understand it, and you won’t earn buy-in until you understand people’s reservations and the reasons behind them.

And in the podcast itself, Maxwell himself goes on to talk about how leaders can hone their craft through introspection, offering sample reflection questions such as:

How open am I to change?

Am I becoming a better listener?

When will I begin to ask more questions?

Can I become comfortable with ambiguity?

Do I rely on my intuition enough?

How adaptable am I as I begin to lead?(my emphasis)

In light of these ideas about listening, understanding and changing one’s own beliefs, perhaps some self-reflexivity is needed when thinking about the anecdote and the leadership principles that Maxwell has shared.

For starters, it’s a known fact that when:

…we hear something that opposes our most deeply rooted prejudices, notions, convictions, mores, or complexes, our brains may become over-stimulated, and not in a direction that leads to good listening. We mentally plan a rebuttal to what we hear, formulate a question designed to embarrass the talker, or perhaps simply turn to thoughts that support our own feelings on the subject at hand.

So there might some degree of bias clouding the interpretation of what the speaker of said anecdote is saying.

Perhaps leaders need to ask:

- Am I hearing what the speaker is saying – but not actually listening to what the speaker is saying?

- Is what the speaker saying what I think it to be, or what it actually is?

The results from this exercise might then turn out to be very different from the reality that has been perceived, especially around the idea of “slow down”.

The phrase might not mean “slow down” or “stop”, and it might not be even about the speaker who utters the phrase.

Leaders might want to consider that “slow down” could well be a polite way of talking about leaders and/or their leadership.

And the phrase itself could well have a multiplicity of meanings, three of which could be:

- Take stock.

Originally, there was an intention to move in a certain direction. However, the organisation seems to be in a different place right now.

Is there a new direction of which people are unaware? Have the objectives shifted – which entails a corresponding shift in execution?

Or worse: Has everyone been doing things wrongly, such that the organisation is way off-course?

- Find a better way.

There needs to be change, but it needs to be done in a better way.People might not know what this is yet, but they do know when things being done at the present moment are not working out.

Can leaders work with people to find that better way, together?

- Streamline.

There are new things that have to be done in order for change to happen.

Correspondingly, there are things that have to carry on being done, because they are a part of the core business.

What are the things that can be done away with, either because they have lost their relevance, or were never relevant to begin with?

A greater focus reduces the feeling of being overwhelmed, which in turn reduces the desire for “slowing down”.

These are but possibilities, of which no certainty is known.

Yet, it is possible for leaders – and, perhaps, Maxwell himself – to be certain of what actually is going on when someone says “slow down”.

But this entails the very act of hitting the brakes – and even coming to a halt.

As Maxwell himself argues, leaders need to be comfortable with the counterintuitive – and, seemingly, counterproductive – ambiguity this creates.

Only then will they be able to, slowly but surely, transform their organisations and the world in meaningful ways that are effective for the fast-changing times.